Crystal Set Receiver

Home made crystal sets played an important role in the evolution of radio broadcasting. “Using a small metal point, called a cat’s whisker, to find the most effective spot” for radio wave detection, home made crystal sets were inexpensive to produce (Sterling, 2002, p. 37). “Hundreds of thousands of hobbyists and the general public” were able to make their own “for the price of a pair of earphones and a few cents’ worth of wire, crystal, and a cat’s whisker” (p. 37). Factory-made radios were not readily available for a few years after World War I, yet home made crystal sets and receivers filled the void.

Shown above is Clarence Morgan’s first crystal set and below, his first receiver, from the early 1900’s.

Home-Made Receiver

Home made crystal sets played an important role in the evolution of radio broadcasting. “Using a small metal point, called a cat’s whisker, to find the most effective spot” for radio wave detection, home made crystal sets were inexpensive to produce (Sterling, 2002, p. 37). “Hundreds of thousands of hobbyists and the general public” were able to make their own “for the price of a pair of earphones and a few cents’ worth of wire, crystal, and a cat’s whisker” (p. 37). Factory-made radios were not readily available for a few years after World War I, yet home made crystal sets and receivers filled the void.

Frequency, Spectrum Scarcity, and Interference

Early legislation, including the Radio Act of 1927 and Communication Act of 1934, were put in place in an attempt to regulate the frequency (wave lengths) allocated to each radio station and how long the station could operate. The frequency space is limited (i.e., spectrum scarcity) and multiple stations using the same frequency created frequency interference (Myers, 2018). Godfrey and Benjamin (2003) write, “by mid-1925, the radio interference problem had become acute” (p. 97). There just were not enough frequencies to meet the demand for them.

Photographs courtesy of Dr. Thomas O. Morgan

Early Radio

Early radios were a very crude ‘cousin’ to today’s satellite radio. Today, we take it for granted that we just have to push a button or use a voice command for a multitude of radio channels to be at played at our convenience. It is a far cry from Morgan’s first radio pictured above.

“By 1922, 382 stations and an estimated 60,000 receivers were in operation, with the number of receiving sets growing to 1,500,000 by 1923” (Hettinger, 1935, p. 1; Myers. 2018, p. 15). The sales of radio receivers “jumped from 750,000 in 1923 to 2,000,000 in 1925, and the number of stations increased to over five hundred broadcasting stations” (p. 16).

RCA and Philco are still familiar names to those who grew up with a transister radio in the house.

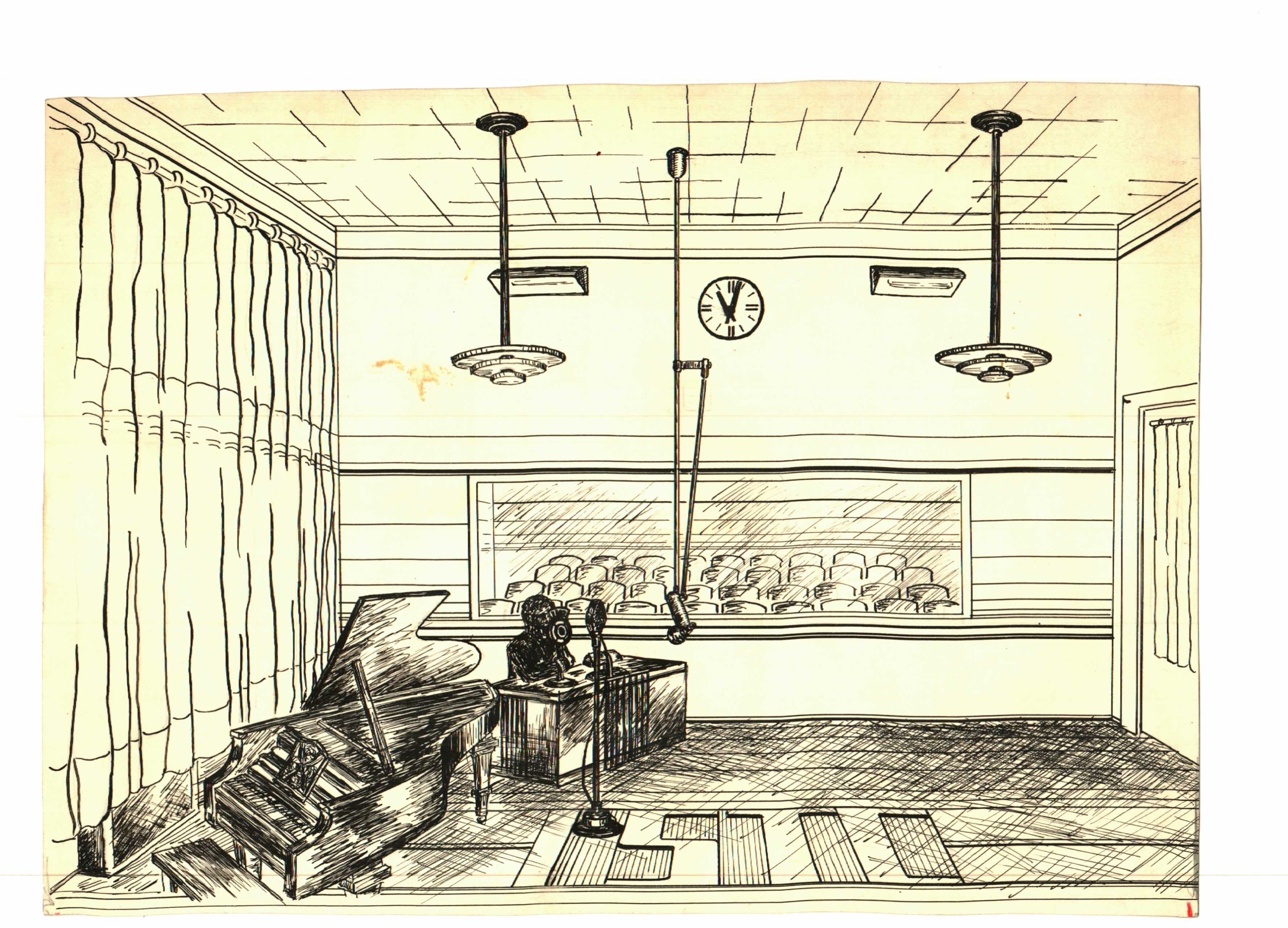

Early Studio Drawing

Audience Rooms

The drawing shown above is a ca. 1934-1936 picture of an innovative radio studio design conceived by Dr. Clarence Morgan. In the background, an ‘audience room’ may be seen as part of the studios. Morgan wanted the listening audience to view his students in action and he also wanted other students to observe and learn from the liver performances.

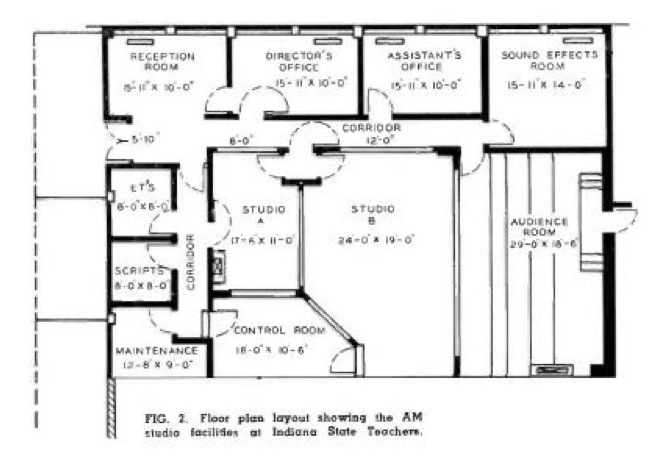

This studio design was consistent in all future radio suites at Indiana State University and the initial outline of Morgan’s 1950’s drawing, shown below, can still be seen today.

1950 Studio

The current radio suite will change with the times, just as Morgan would want it to, at some point in the next year or two. as Indiana State University continues its prestigous legacy of radio broadcasting.

Photograph courtesy of Dr. Thomas O. Morgan

Audience Room drawing used with permission and courtesy of the Indiana State University Archives,

Screenshot of radio studio outline taken from Radio Daily 1951 article by Dr. Clarence M. Morgan.

Philco Radio Dial

The Radio Act of 1927 and the Communication Act of 1934 not only paved the way for creation of the Federal Communications Commission and broadcast cooperatives, they also required all broadcasters to create sustaining programs in the public interest. Sustaining programs were those unsupported by commercials or sponsorships. These programs were not necessarily educational and more like something, as Shepperd, 2017, states, “beyond vaudevillian entertainment that creates a continuity of social experience.”

This was the case with one of the earliest and most well known sustaining programs. The “Music Appreciation Hour” produced by Walter Damrosch was broadcast from 1928-1942 and its format was copied by others (courtesy Library of Congress).

Many of these others were educators working in academic institutions. As an educator, Mrogan believed sustaining programs should not just be entertaining. He created an innovative program strategy that combined education with entertainment, long before the field of entertainment-education (e-e) was in existence.

The programs he and his students broadcast over commercial station WBOW 1230 AM in Terre Haute, Indiana, are listed below.

Research is still being conducted into other possible programs and the end dates of known programs.

Photograph courtesy of Dr. Mary E. Myers

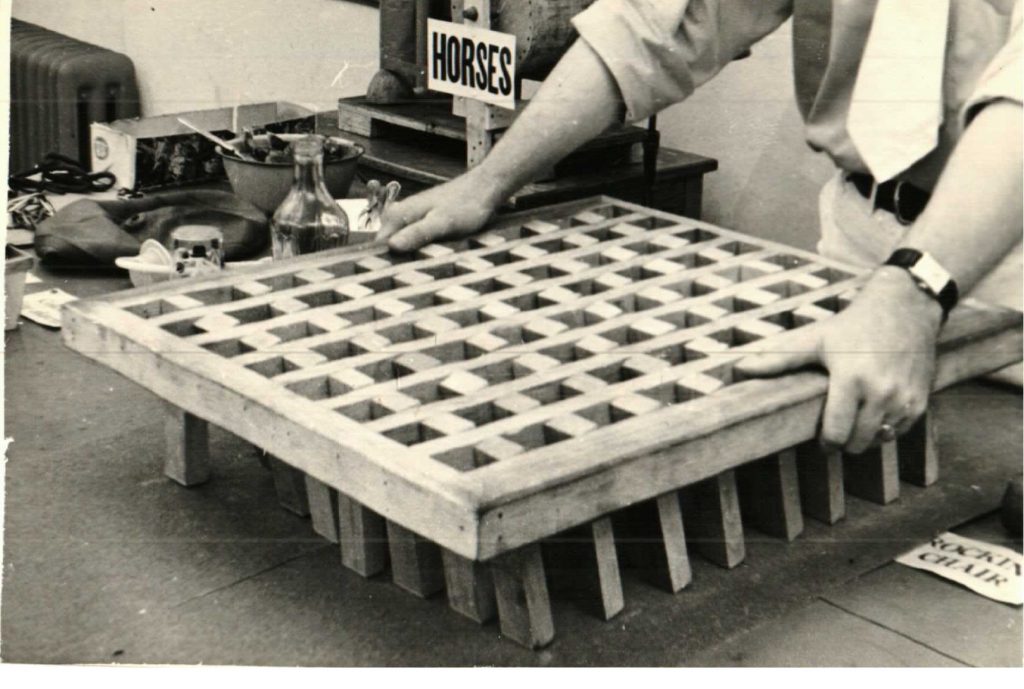

Marching Men

In the years before electrical transcriptions (ETs) and digitized sound effects, many broadcasters were forced to be creative in producing sound to complement the action of a live radio program. Cigarette wrappers made the sound of a wonderful cozy campfire or roaring forest fire, depending on the touch (Morgan, 2017). Pictured above is an early sound effects tool called the “Marching Men,” which was designed by Morgan and built by Indiana State University’s groundskeeper. Depending on how vigorous the movement, the audience heard the sound of a few people walking or an entire army of marching men.

Other devices in Morgan’s arsenal of sound included tools to make the sound of

- horses pulling wagons or cattle over various types of steets

- thunder

- wind

- explosions

- gunfire

- rain

- automobile

- train

- starting motors

- bells of all types from the small school bell to the large fire alarm type

- fire

- doors opening and closing, walking through mud

- the rattle of dishes

- the sound of digging in the earth

- opening of cans

- steamboat sounds

- the sound of men marching

- walking through underbrush

- automobile horns

- airplane noises of various types

- the crash of wrecking automobiles

- a squeaking rocking chair

- a hand pump

- a windmill pumping water

- the sound of climbing stairs

- oars in oarlocks

- the noise of the surf as it rolls upon the shore

- the crash of buildings as in an explosion or earthqueake

- the tom-tom of tribesmen

- the clink of chains

- the popping of corn

- and the echo effects for emphasis on space (Morgan, 1938).

His sound effects laboratory, with its home made tools, was considered to be state-of-the art in 1938, and brought national attention to his work (Myers, 2018).

Photograph used with permission and courtesy of Indiana State University Archives.